Ancient menhirs hold

unchanging truth, locked in stone,

when shall we grasp it.

from Let the Standing Stones Speak

There was no great celebration when I was birthed downstairs in an aristocratic household in 1763, Georgian England. It was all a bit hush hush. My mother was a servant for the landed gentry at the time and while baptismal records reveal that she had been impregnated by a labourer, the father had taken off shortly after stealing her virginity. The talk of the servants’ quarters was that this lad, having been blessed with good looks and an oversized ego, had a reputation for corralling and impregnating women. In short, he had fathered bastards up and down the countryside.

Now it is popularly held that a female bastard was doomed forever, destined to sell her body on the streets of old London Town. However, the family my mother worked for were a pragmatic lot and the Dowager had been heard to say that the child would “grow to provide an extra pair of hands”.

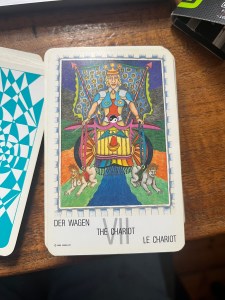

This is exactly what happened! As soon as I was able, I was set to work helping the staff who were, as shows like Downtown Abbey and Upstairs Downstairs make abundantly clear, the backbone, the chariot upon which the upper class of the day rode.

I would have been working there for life but it will come as no great surprise to anyone who has been reading my stories that I ended up in Botany Bay for a run in the colony.

There are a host of romantic yarns about women such as Margaret Catchpole, who was transported to Australia on the Nile, in June 1801, along with yours truly, 95 other women prisoners and a handful of free settlers and their families. She told us a very colourful story about how she had stolen John Cobbold’s coach gelding, and ridden it seventy miles away to London. She was to be hung but her sentence was commuted. We were enthralled as she told us tell how she escaped from Ipswich Gaol using a clothesline to scale the 22-foot wall and entertained us all with all manner of colourful stories.

Call it convenient amnesia if you like, but I am not clear about what bought about this dramatic change in my circumstances. I was obviously not on the Nile as a free settler because I knew Margaret intimately, but I cannot, or will not, recall what I did to deserve this fate. Perhaps our stories have intermingled. However, unlike Catchpole, I am fairly sure that I was never on trial for stealing a horse and I didn’t ever manage to escape from prison or get recaptured. It is a pity because her story is way more romantic than mine.

What I did have in common with Catchpole was that I came to the colony with an invaluable set of skills. She had been a cook and I had been a generally useful servant who could turn her hand to almost anything from being a nurse, standing in as a lady’s maid when one of them ran off, assisting in the stables and helping deliver babies in the village. So, upon arrival neither of us had any problem finding work to keep us occupied until we gained our ticket of leave. We both worked for prominent families who, given the general populace of Botany Bay, didn’t raise an eyebrow about our dark past. By all standards I was regarded to be a very decent lady.

Given the hardships experienced in the early days of settlement it may be hard to fully appreciate that we were actually being given the opportunity to wipe the slate clean and start over. Obviously class differences still existed but it was more egalitarian and there was the possibility to rewrite your story. So when I did eventually get my Ticket of Leave, I had no problem establishing a life that would never have been possible in England.

I married well and worked supporting women during childbirth. I had the support of my husband who was a saddler. The English saddles which came to Australia when the British brought needed to be adapted. As early as 1810 there were wild cattle in the hills around Sydney so bigger knee-pads were needed to do the fast and wild riding necessary to bring the cattle in. My husband was skilled at meeting such needs. He also kitted me out and in doing so enabled me to reach women in more remote parts. Equipped with a horse, saddle and saddle bags I would ride out on my trusty steed, with my saddle bag full of supplies and stay with women for the duration.

Needless to say, when I rode back my Saddle bags were filled with stories and gifts from appreciative women, but there were some other tales that would make your hair stand on end. Sadly no one much was interested in my work. They were all dealing with enough challenges as they mastered life in this new, alien land and there was nothing new about the perils of childbirth. Like the stories of women who were transported for minor crimes the birthing stories have been suppressed, mainly because the subject of pregnancy and birthing was not spoken about – ever. You may smile now, but I was not known as a midwife. Instead, I was regarded to be a very handy woman and my services were highly sought after.

When you have faced the hurdles like those that I faced and traded in birthing you inevitably have numerous encounters with death. Five women on board the Nile were pregnant and it is no exaggeration to say that their pregnancies and deliveries were excruciatingly difficult. It was particularly difficult to be confined to the low spaces between decks, while torrential winds blew and the ship tossed and rolled on the heavy seas. I vividly remember one woman named Mary who gave birth to her sixth child at sea on a particularly stormy night. Mary was had been sentenced to 14 years transportation, for three indictments of larceny, once for stealing a petticoat, a child’s shirt and 6 cakes to the value of 1s 9d. It broke her heart that upon arrival all her children were taken off her and put in orphanages.

Delivery on land was not always that much more straight forward. The thing about childbirth is that even in the best of conditions, when you take every care, things often go wrong during and shortly after the birthing. It was not unusual that mother, infant, or both, would not survive the event. Death in childbirth was sufficiently common that many women regarded pregnancy with dread. In their letters, women often referred to childbirth as “the Dreaded apperation,” “the greatest of earthly miserys,” or “that evel hour I loock forward to with dread.”

In addition to her anxieties about pregnancy, an expectant mother was filled with apprehensions about the death of her newborn child. I was way to pragmatic to subscribe to the notion that women needed “arm themselves with patience and prayer” and to try, during labor, to restrain their groans. I understood the grief associated with birthing a dead baby. and was prepared to meet women’s needs. It goes without saying that I was prepared to offer practical help when women did not want to go through with a pregnancy.

I was certainly not the first to make a herbal abortion tea. Egyptian Pharaohs had written of such things in the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus in 1550bc. Herbal abortion is older than every person living on this planet. It was a way women cared for themselves and one another for a millennium.

Unlike others, who dismissed the natives as savages, I was prepared to seek these wise women out and glean from their knowledge about the native herbs I was not familiar with. For millennia, these people manufactured, utilised and traded mineral medicines. They were almost certainly the first ancient culture to have utilised both sulphur and alum medicinally. In the early days Aboriginal people shared the medical benefits of certain multi-use mineral medicines with the early settlers like me but as they were dispossessed from their lands and tensions escalated, things changed.

I justified dispensing herbal abortions because I believed I was offering a pebble of empowerment. I helped women by giving them complete control and sovereignty over the one thing that was considered their greatest value — fertility. Of course, herbal induced abortions had their risks but so did, knitting needles, crochet hooks and childbirth itself. Women whose husbands, for example, had been away for an extended period did not want to explain their state and were prepared to take the risk. Unlike practitioners today I did not face societal disapproval for helping terminate unwanted pregnancies. No one was particularly concerned. They were more worried about having shelter and keeping food on the table and were way more tolerant of women’s decisions about their bodies.

In addition to assisting in childbirth, I was inevitably called to help deliver the offspring of animals, attended the baptisms and burials of infants. My experimentation with herbs also led me to discover plants that worth brewing into tea. Smilax glyciphylla was used as a medicinal herb by local Aborigines and the colonists also valued it for its health-giving benefits and when brewed produced a saccharine-sweet licorice-flavoured infusion. It came to be known as sweet tea.