“Go inside a stone

That would be my way.

Let somebody else become a dove

Or gnash with a tiger’s tooth.

I am happy to be a stone.

From the outside the stone is a riddle:

No one knows how to answer it.

Yet within, it must be cool and quiet

Even though a cow steps on it full weight,

Even though a child throws it in a river,

The stone sinks, slow, unperturbed

To the river bottom

Where the fishes come to knock on it

And listen.

I have seen sparks fly out

When two stones are rubbed.

So perhaps it is not dark inside after all;

Perhaps there is a moon shining

From somewhere, as though behind a hill—

Just enough light to make out

The strange writings, the star charts

On the inner walls. “

Charles Simic

It is cool and relatively quiet inside this cast iron mould. Having said this, it is reminiscent of being in the womb. Household noise, vibrations, the bark of the dog, the classic music playing penetrates my chamber and, while I am unperturbed by most of the daily happenings in this house, I am comforted by the sound of the birds rising, the Kookaburras laughing, the footfall as she rises, feeds the dog and the kettle signals the first coffee of the day.

Here in my peaceful sanctuary time is not an issue. I have more than enough time to meditate, rummage through fragmental memories. I have no clear memory of the process by which our spirits are assigned new residencies. Clearly, by the time one is back in the womb, or imprisoned inside a statue, all the details of how one was allocated, have been wiped. Unfortunately, those forensic folk, who manage to retrieve corrupted digital data, still haven’t manage to retrieve this information.

It is a mystery that I have never been cast in the role of a luminary, but have been destined to live relatively ordinary lives, to be little more than fly poop. Okay! Before you lecture me on the contribution of each life, I will concede that there has been nothing really ordinary about the roles I have chosen, or, should I say, that the powers that be have determined I should play. One day I will have a serious chat with that creative team.

But I digress! Let me get on with sharing a memory of some note. The details of how I kept ending up in Van Dieman’s Land are blurry, but I distinctly remember being there a number of times in the early days of the colonial settlement. It’s not surprising that I should remember this particular time as there was nothing easy about life then. In fact, I was in a rather desperate situation when on one of his visits to the Port Arthur region looking for convict labour a man, who turned out to be a prominent ship builder looking for labour, spotted me chained to a log.

He asked the officer in charge if I could be unchained and come with him.

Now people talk about chance encounters and the hand of fate and I would have said it was all a lot of nonsense. Bu this encounter was unquestionably one of those life changing moments. The office told this fellow that I could not be unchained because I was a desperate, dangerous character who had tried to escape a few times and that I would be hung if I tried it again. Unbelievably, the man insisted that I come with him to be employed in his shipyards in Hobart.

I worked for Mr John Watson for many years and came to be regarded as one of his best workmen. Sometimes, when I am sitting here inside this cast iron mould, I swear I can hear a tree being felled, can feel the callouses the pit saw imprinted on my hands as I turned the wood from a felled tree into planks, beams, keels and frames. I was a part of a team who built vessels destined to brave wild ocean storms and sail through rocky unchartered coastline.

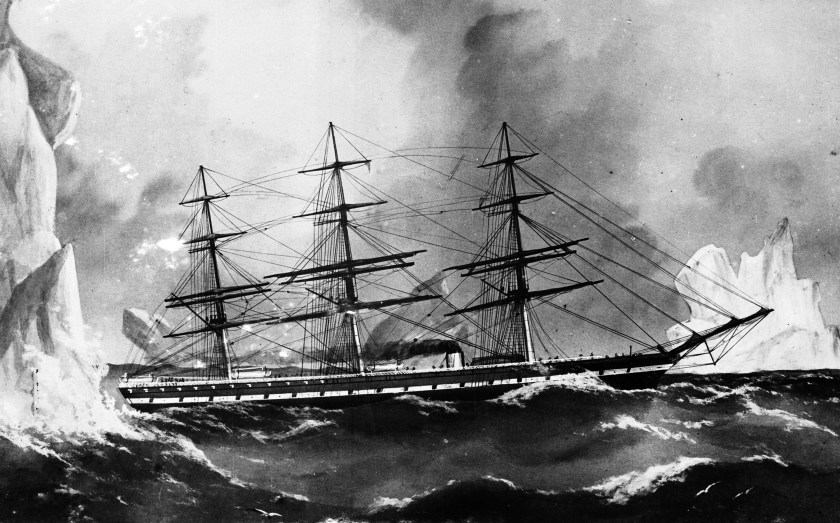

I am not exaggerating when I say that these were not small crafts that we built. We were building fully rigged ships and barques of over 500 tons. Despite what the jerks back home at Lloyds of London would have you believe our ships were strong and fast, which is not surprising when you consider that for many generations the Watsons had been ship builders in Southampton. We puffed with pride when it was said that one of Drake’s ships that was a part of the Armada was Watson built.

It was arduous work for men like me who were tasked with finding trees that would not only provide a good keel but that would fall towards the water. We spent long days, worked from dawn to dusk, chopping, sawing, trimming, finding knees and crooks for certain angles of the boat and carefully shaping them.

One day, when I was asked, by someone in awe of the artistry of our ships, how we turned trees into such proud vessels, I explained that once we had found the right tree, I would spend a long time doing nothing but studying it from every angle. I said that despite being decidedly disgruntled about being felled, once the tree knew what I had in mind it worked with me, gradually revealing a scarcely discernible outline of a keel. As the outline grew stronger, I could see the keel and only then did I begin the painstaking work.

Our joy as the ships, that came to be known as Blue Gum Clippers, were launched was unbridled. The dock in Hobart Town came alive as men and women milled around watching, cheering. It was all very festive and needless to say, after long days in isolation, we went on to celebrate and found recreation in the taverns like the Dusty Miller or the Bird-in-Hand. We had been paid, had money to burn and there were plenty of women willing to help us burn it.

Needless to say, my name has long been forgotten but the names of shipwrights like George and John Watson live on in the maritime history of Tasmania and in the hearts of men like me who they gave a start to. They were responsible for giving me a craft. The respected my art and induced many young men like me, free men, convict men, to become craftsmen, to build ships and take them to sea. They gave us back the lives that seemed to have been taken from us.